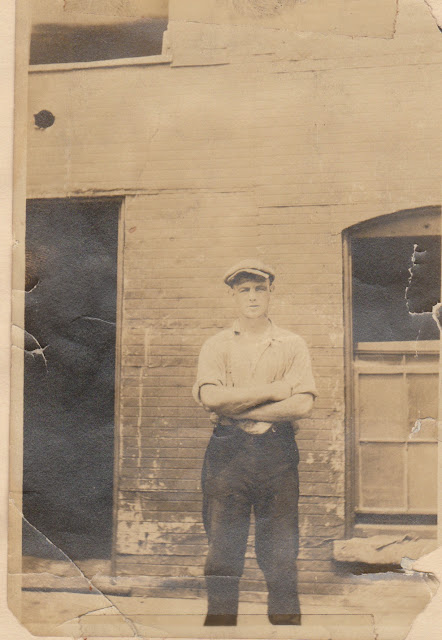

Once considered a national lightweight prospect, Steve

Kennedy was one of the best homegrown boxers to ever come out of Lawrence.

Today his name is known by the few boxing history buffs devoted to the smaller

markets.

|

| Steve Kennedy in South Carolina during WWI |

I’ve heard stories about once famous boxers dying with

nothing but a shoebox full of newspaper clippings. The lucky ones had

scrapbooks. Scrapbooks tell us as much about the subject as they do about the

person who put it together. Often maintained by loving wives, siblings, mothers

or sometime boxers themselves, scrapbooks create a more perfect version of

reality. Missing are reports of those losses most irksome to the boxer. Indiscretions

newspapers were only too happy to report are not included. Sometimes, when the

career has ended and there are blank pages left, the composer will start

filling it with their own personal news. It feels oddly intimate to read these

scrapbooks.

Lawrence lightweight Steve Kennedy’s scrapbook was compiled by

his kid brother, Dan. Twelve years younger than his locally famous brother, Dan

Kennedy would eventually help manage Steve’s comeback attempts during the early

1920s. Few articles were added after 1923. When Steve Kennedy passed away in

the summer of 1931 from tuberculosis, Lawrence papers were quick to publish retrospective

articles on Kennedy for the next two months.

|

| Left to Right: Steve Kennedy, Father, Dan Kennedy (circa 1919) |

Kennedy’s upward trajectory ended after the first four years

of his 13-year boxing career, with the remainder in a sporadic comeback mode. In

1912, Kennedy impulsively pulled out of a golden career opportunity, an unwise

decision made during a bout of youthful homesickness. This decision limited his

boxing prospects to the New England area.

Kennedy began as an amateur in Lawrence, MA. On of his early

opponents, Young Pendergast, made the mistake of calling the 17 year old a

“quitter” after finishing their three round exhibition. Those in charge of the

show, sensing a grudge match, allowed the boys to go three more rounds in which

Kennedy shredded the doubting Pendergast. The gentlemen at the Unity Cycle

Club, Lawrence’s premiere boxing hub, were thrilled with the young prospect but

asked him to come back after he bulked up his then-90 pound frame.

Kennedy proved to be a boxing prodigy and the fistically-sophisticated

audience of his era greatly appreciated his footwork, feinting and his ability

to fight well with both hands.

He earned a devoted fan following and was the darling of the

Unity Cycle Club. Manager Jim Crilley, who was instrumental in creating

Lawrence’s own golden era (1900 – 1920), took over Kennedy’s career and soon he

was fighting big New England names such as the Yelle brothers, Joe Eagan and

Tommy Rawson.

In 1912, local boxing events were less frequent thanks to

the strike-related turmoil in Lawrence. Crilley took Kennedy along with two

other local boys to NYC during what we now call the Bread & Roses Strike. In

NYC, Kennedy won the attention of trainers, fellow boxers and promoters as a

Lawrence Telegram retrospective articles claims, those in “fightdom in the Metropolis do not care a hoot for a game fighter. What

they want and are continually seeking is the class in a boxer’s makeup in

preference to his gameness.”

Crilley brought his boys to the famed Fairmount Gym for

their workouts and they were introduced to visiting star Chicago boxer Packey

McFarland. McFarland was thrilled to make the swift-footed Kennedy a regular

sparring partner. Together with Willie Ritiche a fellow stable mate and

lightweight contender the three men became friendly.

On April 26th Steve fought Charley Twin Miller, a

brother of another boxer he’d recently beaten in match in the Bronx. The story

goes that Packey McFarland asked that Kennedy be added to his fightcard with

Matt Wells. The promoters most excited by Kennedy as a prospect, Pat Donohue

and Billy Gibson wanted to see if the Lawrence kid could maintain his composure

in front of a NYC audience of 15,000. Kennedy held his own and it is said that

for many days the NYC papers were full of talk about the boy from the textile

city or the “Strike City” and cartoons were drawn depicting him either

performing picket duty or being driven along with streets by soldiers with

bayonets.

After witnessing Kennedy’s gym match with Ritchie, Promoters

Donoghue and Gibson saw a potential champion and with some stiffening of his

punches Kennedy could easily takeover Ritchie’s place as premier Lightweight

contender. Donoghue asked Kennedy to have a go at Ritchie the next day and

“clean him up” to which Steve replied “I don’t think it’s fair for met to put

it over this lad, as he and I have been pals on the road and the gym and it

would look raw for me to take him after our being friends all along.” To which

Donoghue responded “Well, you’ll take Ritchie or you’ll take the train for

Lawrence, now which shall it be?”

Later that night, Kennedy, left along at his rooming house,

decided to break curfew and went for a night out in NYC. He had a big scuffle

with Jim Crilley when he returned and Kennedy stalked off back to Lawrence. While

there is no mention of alcohol in the Lawrence Telegram (March 31, 1923) article

that discusses this incident, the Lawrence urban legend has Kennedy coming back

to his room somewhat intoxicated.

According to a 1923 article written by friend and former

trainer Jack Tilley,the NYC promoters tried to get Kennedy to come back but no

amount of pleading telegrams sent to him or his mother would bring him back to

NYC.

He resumed his career in Lawrence in the fall of 1912 and

went on to win the New England Lightweight crown during an era when the

lightweight division was overflowing with talent. His fight with former NE

winner Gilbert Gallant was considered one of Kennedy’s finest moments and was

the subject of conversation for years to come.

No comments:

Post a Comment